Tea with the Queen

Latest topics

Who is online?

In total there are 4 users online :: 0 Registered, 0 Hidden and 4 Guests None

Most users ever online was 253 on Sat Apr 10, 2021 3:06 am

Social bookmarking

Marie-Antoinette and Friendship

3 posters

Page 2 of 2

Page 2 of 2 •  1, 2

1, 2

Marie-Antoinette and Friendship

Marie-Antoinette and Friendship

First topic message reminder :

In her last letter, Marie-Antoinette wrote to her sister-in-law Madame Elisabeth: "Happiness is doubled when shared with a friend...." In those words are contained the value she placed on friendship as being intrinsic to her happiness. Indeed, the queen had a great capacity for friendship, although she was not always prudent in her choice of companions.

In some cases, especially in regard to Madame de Polignac, the friendship spilled over into girlish infatuation. Her enemies seized upon such weaknesses and perceived faults to feed the false rumors that Marie-Antoinette had lovers of both genders. No serious biographer of the queen gives the least credence to the scandalous stories; even Lady Antonia Fraser insists in her recent biography that there is not the slightest indication that Marie-Antoinette ever participated in homosexual acts.

However, people with promiscuous backgrounds tend to judge others according to their own behavior. The French court, being the French court, was the kind of setting that shadowed the most innocent relationships with tawdry connotations. Marie-Antoinette, with her beauty, naiveté and sentimentality, was the perfect target for every sort of calumny.

In an age famous for florid and exaggerated expressions, the queen was especially gushing and emotional when revealing her feelings. In my opinion, it speaks of the deep loneliness and sense of isolation that she experienced as a young girl, sent away from home at the age of fourteen to a hostile court. To some extent, her emotions remained fixed at that age, with all the intensity of early adolescence, as can be seen in the lyrics she wrote for a song, "Portrait Charmant:"

Portait charmant, portait de mon amie

Gage d'amour par l'amour obtenu

Ah viens m'offrir le bien que j'ai perdu

Te voir encore me rappelle à la vie.

Oui les voilà ses traits, ses traits que j'aime

Son doux regard, son maintien, sa candeur

Lorsque ma main te presse sur mon coeur

Je crois encore la presser elle-même

Non tu n'as pas pour moi les mêmes charmes

Muet témoin de nos tendres soupirs

En retraçant nos fugitifs plaisirs

Cruel portrait, tu fais couler mes larmes

Pardonne-moi mon injuste langage

Pardonne aux cris de ma vive douleur

Portait charmant, tu n'es pas le bonheur

Mais bien souvent tu m'en offres l'image

Translation :

Charming portrait, portrait of my friend

Token of love, by love obtained

Ah come and give me back the good I have lost

To see you again brings me back to life

Yes here they are, her features, her features I love

Her sweet looks, her bearing, her ingenuousness

When I press you to my heart

I think I still embrace her herself.

No you don't have to me the same charms

Silent witness of our tender sighs

By recounting our fleeting pleasures

Cruel portrait, you make my tears fall.

Forgive me for my unfair language

Forgive the cries of my bitter woe

Charming portrait, you are not happiness

But so often you give me the image of it.

"Portrait Charmant" was written for one of the queen's close friends, perhaps Madame de Lamballe. It would be unwise to interpret the lines in terms of our contemporary American culture, so colored by Calvinism and yet ready to sexualize everything. In the lifestyle the queen tried to design at Petit Trianon, life was beautiful, love was pure, everything was rustic, pristine, and natural, a place for small children to play in innocence. In her letters she was always covering everyone with kisses, completely unaware of any double entendres, of any sordid misinterpretation.

Why did Marie-Antoinette have such a need for close friendships? In the vast palaces where she was born and raised, amid a many-peopled court, where she often went for ten days at a time without seeing her busy mother, the Archduchess Antonia's closest family member was her sister, Maria Carolina, three years her senior. Maria Carolina was bossy but very motherly and extremely protective of her little sister. When Antonia was about twelve, Carolina married and the two sisters never saw each other again. Later, Marie-Antoinette, far away in France, separated from her mother, who was always highly critical of her anyway, tried to find a friend, a "big sister" to take Carolina's place. Both of her closest friends, Madame de Lamballe and Madame de Polignac, were a few years older than herself and, especially Madame de Polignac, were highly maternal. The queen seemed to grow in emotional maturity and balance after she herself became a mother and had to fight for the survival of her family.

The fact that her marriage had so many difficulties getting started, and that her husband Louis XVI, although a worthy man, was known to be moody, the queen gravitated to her girlfriends for emotional support. Louis XVI had high regard for Madame de Polignac and encouraged his wife to befriend her, seeing her as someone who could guide Antoinette into being a good wife and mother.

Throughout her life, Marie-Antoinette had many friends from all walks of life, including artists, musicians, and theater people, so that her maid Madame Campan in her Memoirs described the queen as being "too democratic." In the last few years, she grew closer to her pious sister-in-law Madame Elisabeth; it was to Elisabeth that the queen, about to die, expressed her last thoughts and her restrained agony. "I had friends," she wrote. "The idea of being forever separated from them and from all their troubles is one of the greatest sorrows that I suffer in dying. Let them at least know that to my latest moment I thought of them."

http://teaattrianon.blogspot.com/2007/09/marie-antoinette-and-friendship.html

In her last letter, Marie-Antoinette wrote to her sister-in-law Madame Elisabeth: "Happiness is doubled when shared with a friend...." In those words are contained the value she placed on friendship as being intrinsic to her happiness. Indeed, the queen had a great capacity for friendship, although she was not always prudent in her choice of companions.

In some cases, especially in regard to Madame de Polignac, the friendship spilled over into girlish infatuation. Her enemies seized upon such weaknesses and perceived faults to feed the false rumors that Marie-Antoinette had lovers of both genders. No serious biographer of the queen gives the least credence to the scandalous stories; even Lady Antonia Fraser insists in her recent biography that there is not the slightest indication that Marie-Antoinette ever participated in homosexual acts.

However, people with promiscuous backgrounds tend to judge others according to their own behavior. The French court, being the French court, was the kind of setting that shadowed the most innocent relationships with tawdry connotations. Marie-Antoinette, with her beauty, naiveté and sentimentality, was the perfect target for every sort of calumny.

In an age famous for florid and exaggerated expressions, the queen was especially gushing and emotional when revealing her feelings. In my opinion, it speaks of the deep loneliness and sense of isolation that she experienced as a young girl, sent away from home at the age of fourteen to a hostile court. To some extent, her emotions remained fixed at that age, with all the intensity of early adolescence, as can be seen in the lyrics she wrote for a song, "Portrait Charmant:"

Portait charmant, portait de mon amie

Gage d'amour par l'amour obtenu

Ah viens m'offrir le bien que j'ai perdu

Te voir encore me rappelle à la vie.

Oui les voilà ses traits, ses traits que j'aime

Son doux regard, son maintien, sa candeur

Lorsque ma main te presse sur mon coeur

Je crois encore la presser elle-même

Non tu n'as pas pour moi les mêmes charmes

Muet témoin de nos tendres soupirs

En retraçant nos fugitifs plaisirs

Cruel portrait, tu fais couler mes larmes

Pardonne-moi mon injuste langage

Pardonne aux cris de ma vive douleur

Portait charmant, tu n'es pas le bonheur

Mais bien souvent tu m'en offres l'image

Translation :

Charming portrait, portrait of my friend

Token of love, by love obtained

Ah come and give me back the good I have lost

To see you again brings me back to life

Yes here they are, her features, her features I love

Her sweet looks, her bearing, her ingenuousness

When I press you to my heart

I think I still embrace her herself.

No you don't have to me the same charms

Silent witness of our tender sighs

By recounting our fleeting pleasures

Cruel portrait, you make my tears fall.

Forgive me for my unfair language

Forgive the cries of my bitter woe

Charming portrait, you are not happiness

But so often you give me the image of it.

"Portrait Charmant" was written for one of the queen's close friends, perhaps Madame de Lamballe. It would be unwise to interpret the lines in terms of our contemporary American culture, so colored by Calvinism and yet ready to sexualize everything. In the lifestyle the queen tried to design at Petit Trianon, life was beautiful, love was pure, everything was rustic, pristine, and natural, a place for small children to play in innocence. In her letters she was always covering everyone with kisses, completely unaware of any double entendres, of any sordid misinterpretation.

Why did Marie-Antoinette have such a need for close friendships? In the vast palaces where she was born and raised, amid a many-peopled court, where she often went for ten days at a time without seeing her busy mother, the Archduchess Antonia's closest family member was her sister, Maria Carolina, three years her senior. Maria Carolina was bossy but very motherly and extremely protective of her little sister. When Antonia was about twelve, Carolina married and the two sisters never saw each other again. Later, Marie-Antoinette, far away in France, separated from her mother, who was always highly critical of her anyway, tried to find a friend, a "big sister" to take Carolina's place. Both of her closest friends, Madame de Lamballe and Madame de Polignac, were a few years older than herself and, especially Madame de Polignac, were highly maternal. The queen seemed to grow in emotional maturity and balance after she herself became a mother and had to fight for the survival of her family.

The fact that her marriage had so many difficulties getting started, and that her husband Louis XVI, although a worthy man, was known to be moody, the queen gravitated to her girlfriends for emotional support. Louis XVI had high regard for Madame de Polignac and encouraged his wife to befriend her, seeing her as someone who could guide Antoinette into being a good wife and mother.

Throughout her life, Marie-Antoinette had many friends from all walks of life, including artists, musicians, and theater people, so that her maid Madame Campan in her Memoirs described the queen as being "too democratic." In the last few years, she grew closer to her pious sister-in-law Madame Elisabeth; it was to Elisabeth that the queen, about to die, expressed her last thoughts and her restrained agony. "I had friends," she wrote. "The idea of being forever separated from them and from all their troubles is one of the greatest sorrows that I suffer in dying. Let them at least know that to my latest moment I thought of them."

http://teaattrianon.blogspot.com/2007/09/marie-antoinette-and-friendship.html

Duchesse de Fitz-James

Duchesse de Fitz-James

From Madame Guillotine: http://madameguillotine.org.uk/2012/01/08/marie-antoinettes-ladies-in-waiting/:

Marie Claudine Sylvie de Thiard de Bissy, Duchesse de Fitz-James (1752-1812) was the daughter of Henri de Thiard de Bissy and his wife Anne Brissart. She was married on 10 January 1769 to Jacques-Charles, Duc de Fitz-James (1743-1805), the elder brother of the Princesse de Chimay.

Madame la Duchesse was chosen to be amongst the first ladies in waiting of Marie Antoinette, although as a new bride it is likely that her duties were not heavy as women in her position were expected to be frequently pregnant and in fact the Fitz-James couple were to have three children: Henriette in October 1770 (this pregnancy probably prevented her from being amongst the group of ladies who travelled to meet Marie Antoinette when she first entered France).

Comtesse de Mailly

Comtesse de Mailly

From Madame Guillotine http://madameguillotine.org.uk/2012/01/08/marie-antoinettes-ladies-in-waiting/:

The third of the most important ladies was Marie-Jeanne de Talleyrand-Périgord (1747-1792), Comtesse de Mailly d’Haucourt. Marie-Jeanne was born on 15th August 1747 in Versailles, the daughter of Gabriel-Marie, Comte de Talleyrand-Périgord (1726-1797) and his wife Marie-Françoise-Marguerite de Talleyrand-Périgord (1727-1758), lady in waiting to Marie Leczinska. Her godparents were the Duc and Duchesse de Mortemart.

She was married on 25 January 1762 to the Comte de Mailly d’Haucourt (1744-1795), a cousin of the famous Mailly-Nesle sisters who had been favourites of Louis XV before he fell into the clutches of Madame de Pompadour. The Mailly couple were very happy together and Madame was extremely popular at Versailles where, like most of the extensive Talleyrand clan she was known for her wit, merry nature and kind heart. Along with the Duchesse de Chaulnes, she was amongst the group of ladies who travelled across France to greet Marie Antoinette upon her first entry into the country and they seem to have become great friends at this time.

Not much is known about Madame de Mailly’s life at court, other than an anecdote from 1770 when her young son died and the then Dauphine, Marie Antoinette had to fight for permission to travel to Paris to visit her grieving lady in waiting and, by now, friend.

After her death in 1792, her husband wasted no time before marrying yet another Mailly cousin, Marie Anne de Mailly-Rubempré (1732-1817) who was much older than himself.

The Prince de Ligne

The Prince de Ligne

With all the misplaced emphasis on Marie-Antoinette's friendship with Count Fersen, it is forgotten that the Queen had many male friends in whom she confided and with whom she corresponded over the years. Then as now, there were people who insisted on seeing impropriety where none existed. One of Marie-Antoinette's most cultured, charming and cosmopolitan friends was indubitably Prince Charles-Joseph de Ligne, from the country now known as Belgium, once a province of the Habsburg empire. The Prince de Ligne had fought in the Seven Years' War on the Austrian side and later became a Field Marshal of the Empire. He was an intimate friend and distant relative of the Habsburg family, especially Emperor Joseph II. The Prince and his wife were the parents of seven children and immensely wealthy. They had vast estates in the Brabant, including marvelous gardens at Bel Oeil. The Prince knew a great deal about horticulture and was able to advise Marie-Antoinette when she was planning her gardens at Petit Trianon. Of Marie-Antoinette, whom he knew quite well, he said: "Her pretended gallantry was never any more than a very deep friendship for one or two individuals, and the ordinary coquetry of a woman, or a queen, trying to please everyone."

The Prince de Ligne was the author of several books, including works of military history. In his personal memoirs he wote extensively of Marie-Antoinette, praising her beauty and her virtue while chivalrously defending her reputation:

Sources: http://teaattrianon.blogspot.com/2012/02/prince-de-ligne.html

The Prince de Ligne was the author of several books, including works of military history. In his personal memoirs he wote extensively of Marie-Antoinette, praising her beauty and her virtue while chivalrously defending her reputation:

The Queen was cautious about gossip due to the infatuations which many gentlemen cherished for her. As the Prince penned many years after her death:The charms of her face and of her soul, the one as white and beautiful as the other, and the attraction of that society hence made me spend five months of every year in her suite, without absenting myself for a single day....

As for the queen, the radiance of her presence harmed her. The jealousy of the women whom she crushed by the beauty of her complexion and the carriage of her head, ever seeking to harm her as a woman, harmed her also as a queen. Fredegonde and Brunehaut, Catherine and Marie de' Medici, Anne and Theresa of Austria never laughed; Marie Antoinette when she was fifteen laughed much; therefore she was declared "satirical."

She defended herself against the intrigues of two parties, each of whom wanted to give her a lover; on which they declared her "inimical to Frenchmen;" and all the more because she was friendly with foreigners, from whom she had neither traps nor importunity to fear.

An unfortunate dispute about a visit between her brother the Elector of Cologne and the princes of the blood, of which she was wholly ignorant, offended the etiquette of the Court, which then called her "proud."

She dines with one friend, and sometimes goes to see another friend, after supper, and they say she is "familiar." That is not what the few persons who lived in her familiarity would say. Her delicate, sure sense of the becoming awed them as much as her majesty. It was as impossible to forget it as it was to forget one's self.

She is sensible of the friendship of certain persons who are the most devoted to her; then she is declared to be "amorous" of them. Sometimes she requires too much for their families; then she is "unreasonable."

She gives little fetes, and works herself at her Trianon: that is called "bourgeoise." She buys Saint-Cloud for the health of her children and to take them from the malaria of Versailles: they pronounce her "extravagant." Her promenades in the evening on the terrace, or on horseback in the Bois de Boulogne, or sometimes on foot round the music in the Orangery "seem suspicious." Her most innocent pleasures are thought criminal; her general loving-kindness is " coquettish." She fears to win at cards, at which she is compelled to play, and they say she " wastes the money of the State."

She laughed and sang and danced until she was twentyfive years old: they declared her *' frivolous." The affairs of the kingdom became embroiled, the spirit of party arose and divided society; she would take no side, and they called her "ungrateful."

She no longer amused herself; she foresaw misfortunes: they declared her "intriguing." She dropped certain little requests or recommendations she had made to the king or the ministers as soon as she feared they were troublesome, and then she was "fickle."

With so many crimes to her charge, and all so well-proved, did she not deserve her misfortunes? But I see I have forgotten the greatest. The queen, who was almost a prisoner of State in her chateau of Versailles, took the liberty sometimes to go on foot, followed by a servant, through one of the galleries, to the apartments of Mme. de Lamballe or Mme. de Polignac. How shocking a scandal! The late queen was always carried in a sedan-chair to see her cousin, Mme. de Talmont, where she found a rather bad company of Polish relations, who claimed to be Leczinskis.

The queen, beautiful as the day, and almost always in her own hair, — except on occasions of ceremony, when her toilet, about which she never cared, was regulated for her, — was naturally talked about; for everybody wanted to please her. The late Leczinska, old before her time and rather ugly, in a large cap called, I think, " butterfly," would sometimes command certain questionable plays at the theatre; but no one found fault with her for that Devout ladies like scandals. When, in our time, they gave us a play of that sort we used to call it the queen's repertory, and Marie Antoinette would scold us, laughing, and say we might at least make known it was the queen before her. No one ever dared to risk too free a speech in her presence, nor too gay a tale, nor a coarse insinuation. She had taste and judgment; and as for the three Graces, she united them all in herself alone. (The Prince de Ligne: His Memoirs, Vol.I, pp 197-201.

The Prince de Ligne's refusal to help the Belgians rebel against the Empire led to the loss of his estates in his native land. He died in Austria in 1814.Who could see her, day after day, without adoring her? I did not feel it fully until she said to me: "My mother thinks it wrong that you should be so long at Versailles. Go and spend a little time with your command, and write letters to Vienna to let them know you are there, and then come back here." That kindness, that delicacy, but more than all the thought that I must spend two weeks away from her, brought the tears to my eyes, which her pretty heedlessness of those early days, keeping her a hundred leagues away from gallantry, prevented her from seeing. As I never have believed in passions that are not reciprocal, two weeks cured me of what I here avow to myself for the first time, and would never avow to others in my lifetime for fear of being laughed at.

But consider how this sentiment, which gave place to the warmest friendship, would have detected a passion in that charming queeu, had she felt one for any man; and with what horror I saw her given in Paris, and thence, thanks to their vile libels, all over Europe, to the Duc de Coigny, to M. le Comte d'Artois, M. de Lamberti, M. de Fersen, Mr. Conway, Lord Stratheven, and other Englishmen as silly as himself, and two or three stupid Germans. Did I ever see aught in her society that did not bear the stamp of grace, kindness, and good taste? She scented an intriguer at a league's distance; she detested pretensions of all kinds. It was for this reason that the whole family of Polignac and their friends, such as Valentin Esterhazy, Baron Bezenval, and Vaudreuil, also Segur and I, were so agreeable to her. She often laughed with me at the struggle for favour among the courtiers, and even wept over some who were disappointed. (Ibid., pp. 201-202)

Sources: http://teaattrianon.blogspot.com/2012/02/prince-de-ligne.html

The Baron de Besenval

The Baron de Besenval

Pierre Victor, baron de Besenval de Brünstatt (1722–1791), the last commander of the Swiss Guards in France, belonged to the Polignac circle and was thus one of Marie-Antoinette's friends. According to Madame Campan:

To quote from Andrew Haggard's biography of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette:The Baron de Besenval added to the bluntness of the Swiss all the adroitness of a French courtier. His fifty years and gray hairs made him enjoy among women the confidence inspired by mature age, although he had not given up the thought of love affairs. He talked of his native mountains with enthusiasm. He would at any time sing the “Ranz des Vaches” with tears in his eyes, and was the best story-teller in the Comtesse Jules’s circle.

It was the yodeling Swiss who described the Queen as having "a wonderful elegance in everything." Unfortunately, his infatuation with her caused her much harm, due to his careless vanity and romantic fantasies. Madame Campan describes a time when Marie-Antoinette was trying to stop a duel between the Comte d'Artois and a courtier, she had Monsieur Campan escort the Baron into a small room attached to her private chambers so she could relay him a message from the King to pass on to Artois. The Baron later exaggerated his descriptions of the encounter, making it sound as if the Queen had invited him into some private love nest. As Madame Campan later wrote:The Duchesse de Polignac and her usual circle would also be often at the Petit Trianon. These comprised the intriguing Comtesse Diane, Mesdames d'Andlau and de Chalon; Messieurs de Guignes, de Coigny, de Vaudreuil, de Guiche, de Polignac, and the Swiss Baron de Besenval, Lieutenant-Colonel Commandant of all the Swiss. Also the Prince de Ligne and the Duke of Dorset formed part of this society, of which the Baron de Besenval is remarkable for two reasons. These are, first, that, although a man of fifty, he was most attractive, a regular coxcomb who sang Swiss songs, yodelled, and made a violent declaration of love to the Queen when alone with her, for which she forgave him; and secondly, for the Memoirs he left behind him. These Memoirs have been largely used by Carlyle in the compilation of his " French Revolution." They were so well written that the enemies of the Baron de Besenval declared that they were written for him, which is quite possible. (Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette by Andrew Haggard, p.148.)

Perhaps the best summation of the Queen's acquaintance with Besenval is in the Tytler biography of Marie-Antoinette:I read with infinite pain the manner in which that simple fact is perverted in M. de Besenval's memoirs. He is right in saying that M. Campan led him through the upper corridors of the chateau, and introduced him into an apartment unknown to him; but the air of romance given to the interview is equally culpable and ridiculous. M. de Besenval says that he found himself, without knowing how he came there, in a plain apartment, but very conveniently furnished, of the existence of which he was till then utterly ignorant. He was astonished, he adds, not that the Queen should have so many facilities, but that she should have ventured to procure them. Ten printed sheets of the woman Lamott's impure libels contain nothing so injurious to the character of Marie Antoinette as these lines, written by a man whom she honoured by kindness thus undeserved. He could not possibly have had any opportunity of knowing the existence of these apartments, which consisted of a very small ante-chamber, a bedchamber and a closet. Ever since the Queen had occupied her own apartment this had been appropriated to Her Majesty's lady of honour in cases of confinement or sickness, and was actually in such use when the Queen was confined. It was so important that it should not be known the Queen had spoken to the Baron before the duel that she had determined to go through her inner room into this little apartment to which M. Campan was to conduct him. When men write upon times still in remembrance they should be scrupulously exact, and not indulge in any exaggerations or constructions of their own. (Memoirs of Marie-Antoinette by Madame Campan, p.104.)

The Baron de Besenval was a man of fifty, whose whitened hair did not interfere with his pretensions to youthful gallantry. His family, though in the last generation Swiss, came from Savoy originally, and his mother was a Pole, a kinswoman of Maria Leczinska's. Besenval was lieutenant-colonel of the Swiss Guards, and so brought into close contact with the Court. He was a rich bachelor, throwing away money upon beautiful things—pictures, statues, bronzes, Bacchantes in white marble. He was a man of the camp as well as of the court, believing in his star, irascible, violent, but knowing when to command himself. He assumed bonhomie and the bluntness of a Helvetic Cincinnati, while he preserved the perfect elegance of a man of the world, and the irreproachable politeness of a grand seigneur. Besenval had a fine marked profile, a well-shaped nose, a small mouth. He was full of insolent grace, stood disdainfully, his hands in his pockets, content with himself, ready to laugh at others.

The Baron de Besenval wrote his memoirs, self-sufficient and unscrupulous as the man himself. His tone in reference to Marie Antoinette is aigredonce. He lets fall a cowardly, base insinuation on the slightest grounds. It was known that his Court favour had suddenly diminished, and only sustained a modified revival. Madame Campan gives an explanation. On a solitary occasion, when the two, Marie Antoinette and the officer, were alone together, the Baron de Besenval was guilty of the insolence of making love to the Queen, who grew furious, and ordered him out of her presence. But certain that he would not dare to repeat the offence, and unwilling to cause an esclandre, she refrained from telling the King, as she had threatened to do, and permitted Besenval, in appearance, to regain something of the old friendly footing, since his position in the Swiss Guards brought him constantly to Court.

Besenval did not survive to perish with his regiment. He died in Paris in 1791. (Marie-Antoinette: the woman and the queen by Sarah Tytler, pp.93-94)

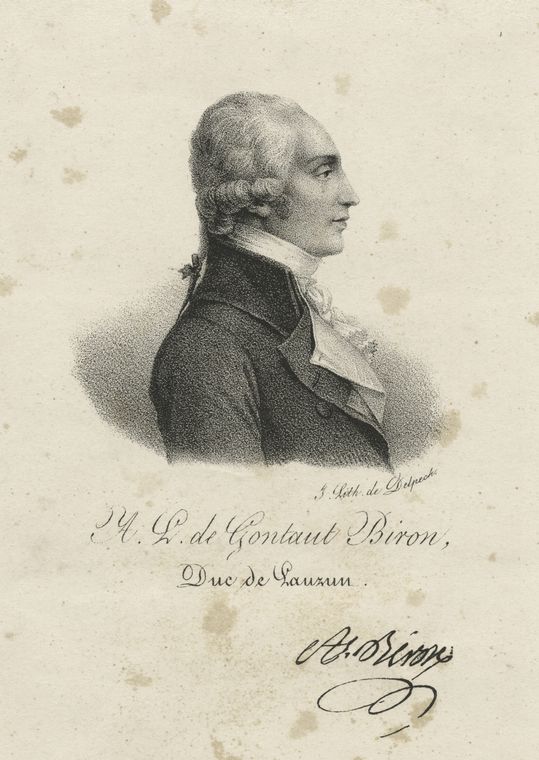

Lauzun

Lauzun

Armand Louis de Gontaut, Duc de Lauzun, later Duc de Biron (13 April 1747 – 31 December 1793) was a military hero and author of a memoir as well as being a courtier at Versailles during the reign of Louis XVI. He could easily have been the model for Valmont in Dangerous Liaisons in that no woman was free from his advances, not even the Queen of France. Sarah Tytler's biography has the best summary of his interaction with Marie-Antoinette:

Armand Louis de Gontant Biron, Duc de Lauzun, was born in 1747, and thus was eight years older than the Queen. He had been reared in the boudoir of Madame de Pompadour, and on account of a difficulty in choosing a tutor for him, a lackey of his late mother's taught him to read. At twelve years of age, he too entered the regiment of the Swiss Guards, knowing that he would succeed to an immense fortune. At nineteen, he married a charming young girl, grand-daughter and heiress of the Maréchal de Luxembourg. Her graces and- virtues won all hearts except her husband's. He came to Versailles when he was twenty-eight years of age, and found the Queen on intimate terms with his friend the Princesse de Guéménée, who procured him the introduction which he coveted, and he received some kindness from Marie Antoinette. A race, in which his horse was ridden by a child, made him fashionable; and at the Queen's request, other races were arranged.

Lauzun was a French Lovelace, an avowed womankiller, with all the immoderate vanity and odious heartlessness of such a character. He ran after those women who were much in the public eye—grandes dames, famous beauties, celebrated actresses. To throw on queens themselves bold looks—to make the proudest hearts beat, were it only with indignation —to cause the most glorious eyes to shine, if but with anger—to excite the jealousy of the salon, the envy of the men, the ecstacy of the women, was his chief ambition. And this very fine gentleman had the weaknesses of a fine lady, and carried them off admirably. He could weep ostentatiously, without looking ridiculous; he changed colour like the Comtesse Diane, who had an inconvenient habit of blushing like a school-girl; he even fainted when it was desirable to produce a sensation.

Marie Antoinette had no great liking for Lauzun, yet she regarded his vices with a certain foolish interest and curiosity—feelings which such mauvais sujets, as she knew him to be, are apt to excite in women like her. Mercy wrote of him as one of the dangerous young fools to whom the Queen gave too free access; but the Comte added no hint that could support the outrageous fatuousness of the Duc de Lauzun's assertion of the Queen's favour. Lauzun, on his part, had no special regard for Marie Antoinette; but the role of admirer of the first woman in France pleased his coxcombry, and, as he fancied, mortified les grandes dames.

Suddenly a lively sensation was excited at Court by the incident of "the heron's plume," told in two very different ways. One day Lauzun appeared at Madame de Guemenee's in uniform, with a snowwhite heron's plume in his casque. Some evenings afterwards, the Queen showed herself with the same unique plume in her head-dress. Lauzun's vapouring statement was, that the Queen had said to Madame de Guéménée that she, Marie Antoinette, was dying to have the heron's feathers, which he sent to her accordingly through his obliging ally. The Queen, he added, not only wore the plume, but appealed to him as to what he thought of it in her head-dress, and declared she had never found herself adorned so much to her mind. The Duc de Lauzun then wrote down a cock-and-bull version of an interview he had with the Queen, when she insinuated her attachment to him, and, but for the restraint he put upon himself, .would have expressed her regard openly.

Madame Campan's explanation has the merit of being credible. The Queen had rashly admired the rare plume, when the Duc de Lauzun at once offered it to her through Madame de Guéménée. The offer embarrassed Marie Antoinette, who did not see how she could refuse it, or accept it without presenting Lauzun with an equivalent—a course to which there were many objections. On the whole, it seemed the best plan to take the feathers as a matter of course, let their former owner see her wear them once, and then suffer the subject to drop. But her imprudent condescension to such a man bore its natural fruits. The Duc de Lauzun solicited an audience, and Madame Campan, who was in the next room in the performance of her duty, again heard the Queen's voice raised in anger. "Go, sir," were the words she said this time, and when her dismissal was obeyed, she protested to her bed-chamber woman," That man shall never again come within my doors." As an established fact, the Queen from that date testified her displeasure and dissatisfaction with the nobleman. When the Maréchal de Biron died, the Duc de Lauzun, the heir of his name, desired the post of colonel of the French Guards, but the Queen prevented his nomination, procuring the commission for the Duc de Chatelet. For that matter, Lauzun had been unmasked to her by Mercy and the Abbé as early as 1777. Lauzun was overwhelmed with debt, in consequence of his reckless life and prodigal extravagance; though he had started with a hundred thousand crowns rent, he owed two millions. Madame de Guéménée importuned Marie Antoinette in vain for lettres d'etat, to save the spendthrift from his creditors. It is equally well known that the disappointment of his unwarrantable expectations threw the Duc de Lauzun into the faction of the Duc d'Orleans, and converted the Queen's pretended admirer into a bitter enemy both of her and the King.

....It is saying little to note that [Marie-Antoinette] had many enemies. She had managed to pique and alienate some of the representatives of the greatest houses in the kingdom—such as "the Montmorencies, the Clermont-Tonnerres, the Rochefoucaulds "—by the constant injudicious display of her preference for her private friends; above all, for Madame de Polignac and her set—a line of conduct against which Mercy had warned the Queen to no purpose. For some time, as her old friend and adviser had not failed to point out, her weekly balls, when the Court was at Versailles, had been ominously ill-attended. The great families did not care to come from Paris and find the Queen so engrossed by a bevy of favourites and her own amusement as hardly to take the trouble, in spite of her naturally gracious manners, to "hold a circle," and take due notice of her guests. Besides, these offended magnates were by no means without skeletons in their own cupboards, and felt further insulted by some painfully honest speeches of the young Queen's, such as, "I do not care to receive wives who are separated from their husbands."

There is no question that the first calumnies against the Queen arose in the salons, and tempted every unworthy fine gentleman, who listened to the sneers and doubles entendres, and believed in them, to profess insolently to appropriate Marie Antoinette's frank smiles and ready kindness.

The Duc de Lauzun fought well in La Vendée against the defenders of the altar and the throne; but his comrades could not forget or forgive his birth and assumption of superiority. He was guillotined on the 1st of January, 1794. It is said that on the scaffold he declared, "I have been false to my God, to my order, and to my King." The Duc de Lauzun, like the Baron de Besenval, left behind him memoirs, the authenticity of which, though at first questioned with indignation by his greatest friend, Talleyrand, is now universally admitted. The only testimony against the good name of Marie Antoinette which could be for a moment entertained by any reasonable person, is contained in the malicious inferences and vindictively-garbled statements of these two noble braggarts, who proclaimed to the world what, if true, it would have been the height of treachery in them to reveal, but which, as it is, bears its foolish falsehood on its brazen face. (Marie-Antoinette, the Woman and the Queen by Sarah Tytler, pp. 95-98)

Sources: http://teaattrianon.blogspot.com/2012/03/lauzun.html

Madame Auguié

Madame Auguié

Adélaïde Genet, Madame Auguié (1758-1794) was one of the last maids of Marie-Antoinette, a sister of Madame Campan. She tried to save Marie-Antoinette's life but later took her own. (From Madame Guillotine http://madameguillotine.org.uk/2010/05/16/la-belle-madame-auguie-and-her-daughters/ via Vive la Reine http://vivelareine.tumblr.com/post/19159225156.)

Madame Vigée-Lebrun, who knew both Madame Auguié and her sister, Madame Campan very well described Adélaïde thus: ‘I have known few women as beautiful and as agreeable as Madame Auguié. She was tall with an attractive figure; her face, with its complexion of peaches and cream, was fresh, and her pretty eyes shone with gentleness and kindness.’

Marie Antoinette was very fond of Adélaïde Auguié and referred to her by the nickname ‘my lioness’, in tribute to her unusual height and proud bearing. The Queen’s fondness for her femme de chambre was fully repayed on the night of 5th October 1789 when Adélaïde was one of the two ladies who kept vigil outside the Queen’s bedchamber and raised the alarm when the mob broke into the palace. It was Adélaïde Auguié who ran to the guardroom to see the blood covered guardsmen there then ran back to her mistress’ bedchamber to wake her up with the cry ‘Madame, you must get up at once!’ before helping the bewildered Queen from her bed and escaping with her down the corridor that led to the King’s apartments. In gratitude for her services on that night, Marie Antoinette bestowed on Madame Auguié one of the splendid and immense nécessaire cases that were made for the escape to Varennes.

Along with Madame Campan, Adélaïde remained with the royal family until the very end, leaving only in August 1792 when they left the Tuileries and were taken to the Temple. Faithful, loyal Madame Auguié’s final act for her mistress was to slip her 25 Louis, knowing that money would now be in short supply for the beleagured, unfortunate Queen.

Sadly, Madame Auguié was so distressed and overset by the execution of her former mistress, Marie Antoinette and so terrified by the prospect of her own inevitable arrest that she committed suicide by self defenestration on the 26th July 1794, leaving two young daughters: Aglaé (1782-1854) who would marry the celebrated Marshal Ney on the 5th August 1802 and Adèle, later Madame de Broc, who was to be best friends with Hortense de Beauharnais.

Sources: http://madameguillotine.org.uk/2010/05/16/la-belle-madame-auguie-and-her-daughters/

http://vivelareine.tumblr.com/post/19159225156

Madame de Saulx-Tavannes, Lady-in Waiting

Madame de Saulx-Tavannes, Lady-in Waiting

From http://vivelareine.tumblr.com/post/53074109054:

A portrait of Marie-Éléonore-Eugénie de Lévis de Châteaumorand, the comtesse de Saulx -Tavannes, by a French school artist. Circa 1760.

She was a lady-in-waiting to Marie Antoinette from 1774 to 1785; in 1785 she retired from her position in favor of her daughter, Gabrielle.

image source: Cornette de Saint-Cyr

This lady was several years older than the Queen and it sounds like she was left over from the old court of Marie Lesczysnka.

Re: Marie-Antoinette and Friendship

Re: Marie-Antoinette and Friendship

Louise of Hesse-Darmstadt, one of Marie-Antoinette's childhood companions, with whom she corresponded.

http://teaattrianon.blogspot.com/2013/10/louise-of-hesse-darmstadt.html

http://teaattrianon.blogspot.com/2013/10/louise-of-hesse-darmstadt.html

Re: Marie-Antoinette and Friendship

Re: Marie-Antoinette and Friendship

Elena wrote:I can't find a picture of him, but he is a friend to whom Marie-Antoinette wrote a great deal during the Revolution. Here is what the 1910 Encyclopedia Britannica says of him:Source: http://books.google.com/books?id=rkBTAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA795&lpg=PA795&dq=Count+Valentine+Esterhazy&source=bl&ots=lOZwGYRqwn&sig=x-XPJlamPfMM-AcOK1GIUt-fGzs&hl=en&ei=0DLUTrHjFqnW0QGZ1qiSAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBsQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q=Count%20Valentine%20Esterhazy&f=falseCount Balint Miklos (1740-1805), son of Balint Jozsef, was an enthusiastic partisan of the duc de Choiseul, on whose dismissal, in 1764, he resigned the command of the French regiment of which he was the colonel. It was Esterhazy who conveyed to Marie Antoinette the portrait of Louis XVI. on the occasion of their betrothal, and the close relations he maintained with her after her marriage were more than once the occasion of remonstrance on the part of Maria Theresa, who never seems to have forgotten that he was the grandson of a rebel. At the French court he stood in high favour with the comte d'Artois. He was raised to the rank of maréchal de camp, and made inspector of troops in the French service in 1780. At the outbreak of the French Revolution, he was stationed at Valenciennes, where he contrived for a time to keep order, and facilitated the escape of the French emigrés by way of Namur; but, in 1790, he hastened back to Paris to assist the king. At the urgent entreaty of the comte d'Artois in 1791 he quitted Paris for Coblenz, accompanied Artois to Vienna, and was sent to the court of St Petersburg the same year to enlist the sympathies of Catherine II. for the Bourbons. He received an estate from Catherine II., and although the gift was rescinded by Paul I., another was eventually granted him. He died at Grodek in Volhynia on the 23rd of July 1805.

See Mémoires, ed. by E. Daudet (Fr.) (Paris, 1905), and Lettres (Paris, 1906).

The English Historical Review, Volume 23 says:http://books.google.com/books?id=krDRAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA204&lpg=PA204&dq=Count+Valentine+Esterhazy+Marie-Antoinette&source=bl&ots=3ywnOCKfVY&sig=NkICIq3tigv9-StJr_lxiU8eaSg&hl=en&ei=6TXUTtLDNKX00gHYmvCRAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&sqi=2&ved=0CCIQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Count%20Valentine%20Esterhazy%20Marie-Antoinette&f=falseIt cannot be said that the Lettres du Comte Valentin Esterhazy de sa Femme, 1784-1792, which M. Ernest Daudet has edited, with an introduction and notes (Paris: Plon, 1907), add much to our knowledge of the reign of Louis XVI. Count Valentine Esterhazy was a friend of Marie Antoinette and an officer in the French service. He was not clever, nor had he the genuine Frenchman's gift of style. He seems to have been an exemplary husband, much attached to his dear Fanny and their children. Scraps of English here and there remind us of the then fashionable Anglomania. In one letter he complains of the inflation of military charges, 'due to our bureaucracy, the proper name for our administration.' In another he mentions how carefully he read Rousseau's Emile, and marked the best passages with a view to the education of his expected son. But down to 1786 his letters record little save the routine business and amusements of his profession and class, without a glance beyond the pleasant surface of things. After 1786 there is a gap in the correspondence until 1790, when the count emigrated. He attached himself to the party of the princes, who sent him at the end of 1791 to enlist the support of the empress of Russia. Esterhazy has much to say of Catherine's noble sentiments, magnificent hospitality, and industry as a playwright. He was astounded at the wealth and profuse splendour of the Russian nobles. St. Petersburg impressed him much, and Moscow more, but he did not excel in description. His business did not go forward. He lamented the cabals among the emigres and the coldness of the powers nearest to France. He perceived that Austrian statesmen were not sorry to see France disabled, as they thought, from taking an active part in European affairs, although he did not suspect that Catherine was chiefly anxious to find distractions for her own rivals. Foreign intervention, he believed, would remedy all the ills of France, if only it were prompt and vigorous. The real force of the revolutionary movement he seems to have understood as little asdid the generality of his brethren in misfortune. M. Daudet makes a singular mistake in implying (p. 872) that Louis XVI declared war against the emperor in December 1791. What Louis then did was only to menace the elector of Treves with armed constraint if the corps of emigres did not disperse.

More here:

http://books.google.com/books?id=u7GTMH8lFA8C&pg=PA272&lpg=PA272&dq=Count+Valentin+Esterhazy+Marie-Antoinette&source=bl&ots=i22LaJWtAb&sig=W_H7GMaHl9sXqzZ4fWlG_dM1oME&hl=en&ei=cjrUTo3lHqjg0QH05OHfAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4&sqi=2&ved=0CCYQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=Count%20Valentin%20Esterhazy%20Marie-Antoinette&f=false

and here:

http://maria-antonia.justgoo.com/t110-le-comte-valentin-esterhazy

If anyone has a picture or more information, please share it!

Thanks to Sophie for this picture:

And info: https://archive.org/stream/lettresducteval00daudgoog#page/n7/mode/2up

https://archive.org/stream/mmoriesducteval00daudgoog#page/n7/mode/2up

Page 2 of 2 •  1, 2

1, 2

Similar topics

Similar topics» Marie-Antoinette in Art

» Family: The Habsburgs

» Marie-Antoinette and Style

» Recognition by the Church of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

» Marie-Antoinette's Letters

» Family: The Habsburgs

» Marie-Antoinette and Style

» Recognition by the Church of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

» Marie-Antoinette's Letters

Page 2 of 2

Permissions in this forum:

You cannot reply to topics in this forum

» Recognition by the Church of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

» Reposts: In Praise of Monarchy!

» Remembering Louis XVI

» Mass for Louis XVI on live video

» Judges 17:6

» War in the Vendée/Guerre de Vendée

» The Comte de Chambord (Henri V)

» Reflection: Les Membres et L'Estomac